III. La fotografía como viaje

Como parte de la muestra Sin tierra, pero también con cierta autonomía para alcanzar otros horizontes y por otros medios, Rafael Guendelman creó el libro (Sin tierra). Se trata de un artefacto curioso. A primera vista, sus materiales y tamaño nos indican que estamos ante un libro común. Pero al abrirlo descubrimos que sus páginas no están cocidas, sino que forman una sola gran banda de papel que ha sido plegada como una suerte de acordeón (estirada alcanza casi dos metros) y que puede separarse de otra banda de papel más grueso que forma las tapas y solapas que protegen a este curioso libro. La banda lleva impresas por uno de sus lados una serie de fotografías en varios tamaños, que fueron tomadas por el artista en una estadía de siete meses en Cisjordania, durante el año 2012. El libro incluye además un breve texto del propio Guendelman, un índice que nos revela las coordenadas del lugar donde fue captada cada fotografía y un sencillo mapa que muestra la distribución de aquellos lugares en Cisjordania.

En cuanto libro, pertenece al género llamado «libro de artista». Se trata de una publicación cuyo fin es tanto la comunicación de un contenido como el constituir un objeto que tenga valor por sí mismo. Sus aspectos formales y estrategias retóricas han sido trabajados como una obra de arte, pero a la vez se mantienen ciertas características normales de un libro, tales como su apariencia, su carácter compacto y portable y el hecho de formar una edición (800 ejemplares). El énfasis en el carácter objetual y modulable es notorio. La banda de fotografías plegadas en acordeón nos relaciona con este objeto desde en una dimensión maleable y modulable que no solemos experimentar con los libros (salvo que se trate de un pop-up, por ejemplo). Esta banda podemos extenderla y pegarla en una superficie lisa o con ángulos, o bien disponerla como un acordeón más o menos apretado de tal modo que se sostenga por sí mismo como un objeto que se extiende en el espacio tridimensional. Es el lector, usuario u espectador quien decide el modo en que se relacionará con este artefacto.

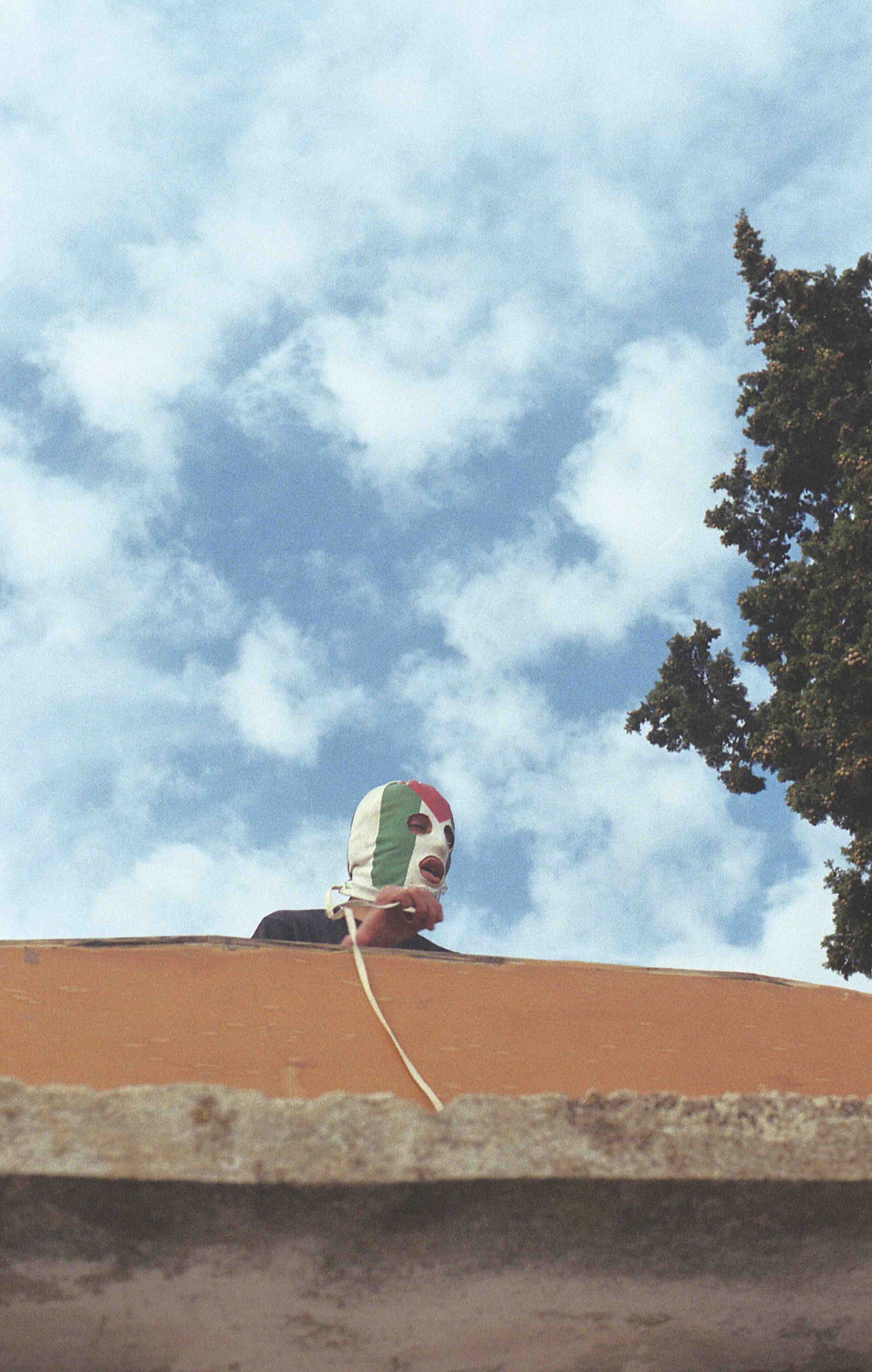

Las fotografías análogas que componen el libro suponen otro momento de este artefacto. Ellas nos muestran escenas mínimas por lo general. Sean retratos de niños o militares, sea un paisaje urbano o rural, sea una concentración callejera o una barricada, todas son situaciones o puntos de vista oblicuos, fuera de la noticia y de la gran historia. No hay en ellas la urgencia de la denuncia que suele ser la mirada dominante de las imágenes que circulan de Palestina. En cambio, hay una mirada curiosa, errante, algo distraída e incluso azarosa, capaz de perderse en detalles cotidianos y luego reencontrarse con la contingencia. Abundan las murallas, rejas y torres de vigilancia de este «espacio a medio camino entre un campamento de refugiados y un país» que sería Palestina en palabras de Guendelman.

La mirada que se estructura resulta propiamente fotográfica en lo que tiene la fotografía de huella y de captura. La huella de algo que existió y reflejó la luz de cierta manera, así como la huella de la experiencia y la mirada que dispusieron una cámara y un punto de vista. La captura de un tiempo otro, ahora convertido en un momento eterno, como tiempo que se ha vuelto una materia tangible. Como dice Susan Sontag, la fotografía es al mismo tiempo un modo de certificar y rechazar la experiencia. Y el artista nos confirma este carácter desde la experiencia de capturar estas fotografías: «el registro análogo, gracias a la dificultad de rehacer las fotografías y a su resistencia ante cualquier condición climática (bendita Zenit DF300), me permitió utilizar la fotografía más que como un medio de comunicación, como una herramienta de orientación espacial: un cuaderno de anotaciones y una extensión del mapa mental hacia el paisaje recorrido».

III. Photography as travel

As a part of the No Land exhibition, but with certain autonomy so as to reach other horizons and through other means, Rafael Guendelman created the book (No Land), a curious artifact. At first glance, its materials and size indicate that we’re standing before a common book. But upon opening it, we discover that its pages aren’t sewn together, but rather, they form part of a single long paper banner that has been folded into an accordion of sorts (stretched out, its length reaches almost two meters). On further investigation, we find that this can be separated from another thicker paper banner, which serves as the book jacket that protects this curious book. The inner banner has a series of photographs printed on one side of the paper, all pictures that the artist took during a seven-month stay in the West Bank during the year 2012. The book also includes a brief text by Guendelman himself, an index that reveals coordinates for the place where each photograph was taken, and a simple map that shows the distribution of these places throughout the West Bank.

As for the book, it belongs to the genre called “artist’s book”: a publication whose objective is both to communicate a certain content, as well as to constitute an object that has value in and of itself. Its formal aspects and rhetorical strategies have been worked as a piece of art, but at the same time, certain common book characteristics are kept, such as its appearance, its compact and portable nature, and the fact that it is part of an edition (800 copies). The emphasis on its objectual and malleable character is notorious. The banner of photographs folded into an accordion allows us to relate to this object from a moveable and adjustable perspective that we seldom experiment with books (unless we are dealing with a pop-up book, for example). This banner can be extended and attached to a flat or angular surface, or also be set up as a more or less compact accordion so that it may hold itself up as an object that extends into three-dimensional space. The reader, user or spectator is whom decides the manner in which he or she shall engage with this artifact.

The analog photographs printed within the book entail one more of this artifact’s moments. In general, the images depict minimal scenes. Whether they are portraits of children or soldiers, urban or rural landscapes, street concentrations or barricades, these are all oblique situations or points of view, removed from the daily news and from the great story. These pictures lack the urgency of condemnation that is often the dominating perspective of the circulating images of Palestine. Instead, there’s a curious, wandering, somewhat distracted and even random point of view, one that is capable of getting lost in everyday details and then rediscovering the issues at hand. There is an abundance of walls, fences, and watchtowers in this “place that is halfway between a refugee camp and a country”, that in Guendelman’s words, is Palestine.

The perspective turns out to be inherently photographic, considering how photography has notions of both trace and capture. The trace of something that existed and reflected light in a certain way, as well as the trace of the experience and the perspective that was disposed by a camera and a point of view. The capture of a different time, now turned into an eternal moment, like time that has turned into tangible matter. As Susan Sontag says, photography is both a manner of certifying and rejecting experience. The artist confirms this nature from the experience of capturing these photographs: “Registering analogically, thanks to the difficulty of re-taking photographs and to its resistance under any sort of climatic conditions (blessed Zenit DF300), allowed me to use photography as more than a means of communication, but rather, as a tool for spatial orientation: a notebook and an extension of a mental map towards the traveled landscape.”