I. Líneas de un conflicto

Si buscamos en internet información que nos explique el conflicto entre palestinos e israelíes, en algún momento nos cruzaremos con diversos mapas en los que intrincadas líneas diferenciadas por colores o intervalos se cruzarán una y otra vez. Con ellos intentarán explicarnos el límite entre el estado árabe y el judío según el reparto de las Naciones Unidas de 1947, la Línea Verde del armisticio de 1949, las tierras ocupadas tras la Guerra de los Seis Días, las zonas bajo administración palestina tras los Acuerdos de Oslo o el muro que Israel ha construido en Cisjordania desde el 2002, entre otras posibilidades.

Cada línea representa una convención, un acuerdo o una postura. Se trata de líneas que representan puntos de vista por los cuales se llega a matar y morir. A 13 mil kilómetros, a dos continentes y un océano de distancia, aun acá esas líneas significan realidades antagónicas para muchos de los herederos y simpatizantes de la comunidad árabe y la comunidad judía de este rincón de Sudamérica. Cabe recordar, y volveremos sobre ello, que en el territorio del estado de Chile vive la comunidad de palestinos más grande fuera del Medio Oriente.

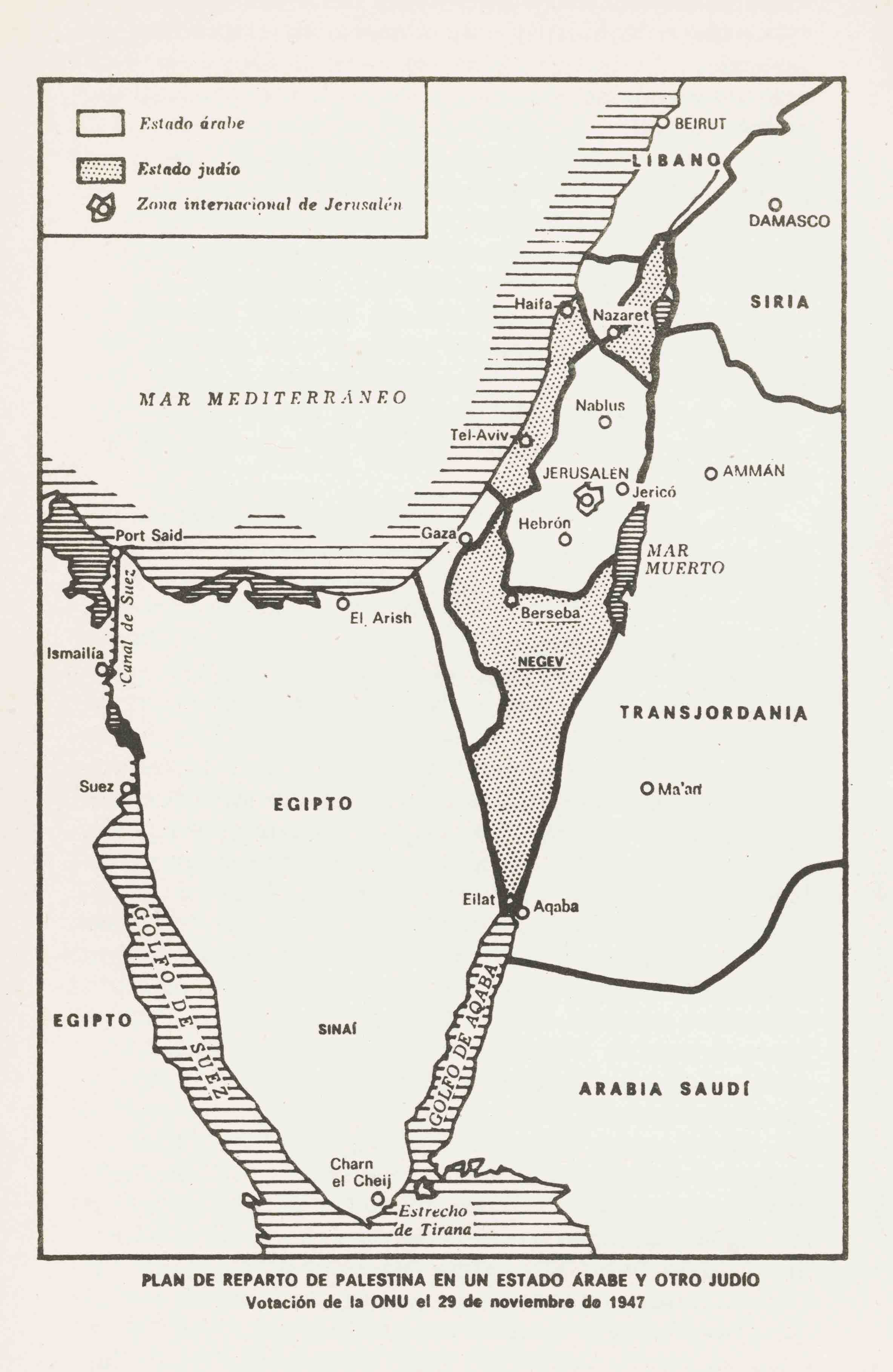

Repasemos las principales «líneas» de este conflicto y hagamos un poco de historia. La primera línea importante es la que definió el reparto de Palestina (ocupada por Gran Bretaña desde el fin de la Primera Guerra Mundial y antes por el Imperio Otomano), se determinó en la reñida votación del 29 de noviembre de 1947 en la recién creada Organización de Naciones Unidas y definió la creación de dos estados en este territorio: uno árabe y otro judío. El reparto era el resultado de causas relativamente heterogéneas: el apuro de Gran Bretaña por retirarse (su mandato había resultado un fracaso, y cada vez era más difícil controlar la violencia entre las comunidades palestina y judía); los complejos negociaciones diplomáticas de un mundo que recomponía sus poderes y equilibrios tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial (desde la desarrollada por la Agencia Judía hasta el repentino poder de negociación que adquirieron países del tercer mundo al verse involucrados en la votación); por último, el mundo aún no se reponía ―¿cómo podría haberlo hecho?― del impacto que causó el exterminio de más de seis millones de judíos en la Alemania nazi, lo que otorgaba un sentido de urgencia y compensación a la creación de un estado judío. Se coronaba así medio siglo de acción del movimiento sionista, que desde el siglo XIX había luchado por la creación del estado de Israel.

Con tal apuro y con causales tan diversas, el reparto de 1947 estaba destinado al conflicto o al fracaso. Entregaba el 57 % de Palestina a un nuevo estado judío en el que más de la mitad de la población era árabe y dejaba a Jerusalén (ciudad santa para judíos, cristianos y musulmanes) bajo tutela de la ONU. Por supuesto que los líderes de los 1.200.000 palestinos que vivían en los territorios que a miles de kilómetros se estaban repartiendo no aceptaron esta división. Como tampoco lo hicieron los países árabes. Así, el mismo día en que se retiraron las tropas de Gran Bretaña, se inició una cruenta guerra entre el recién creado estado judío y los ejércitos de Transjordania, Egipto, Siria e Irak, además de milicias irregulares y contingentes menores del Líbano, Arabia Saudí y Yemén, todos países que no reconocieron al recién creado estado de Israel.

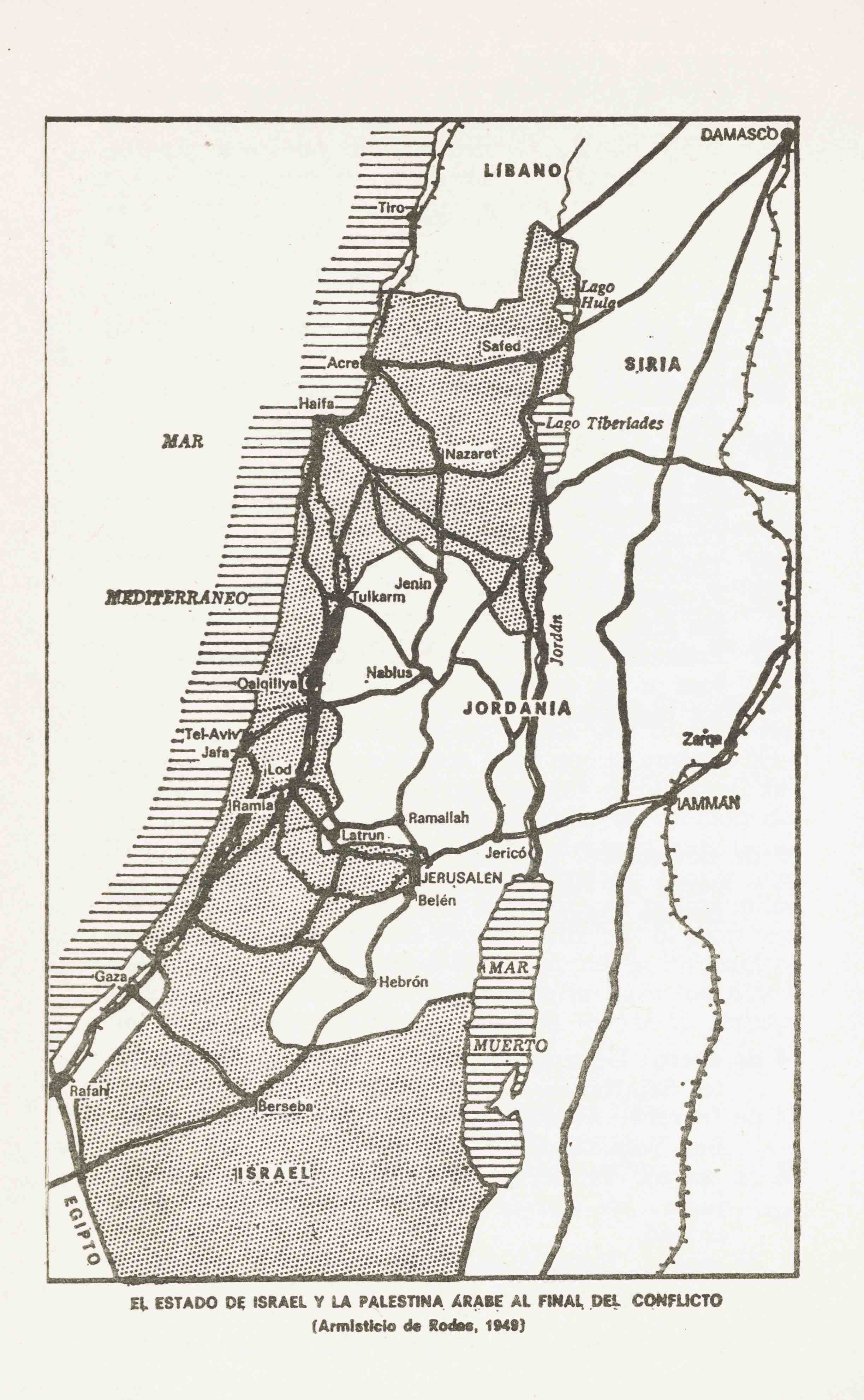

Las hostilidades no se detuvieron por completo hasta un año después, y a esa altura la victoria de Israel era clara. La línea verde definida por el armisticio aumentó su territorio en un 23 % respecto del reparto original de la ONU y, a pesar de que sólo mantuvo una parte de Jerusalén y no logró conquistar la amurallada «ciudad vieja», declaró a esta ciudad como su capital. Los restos del estado palestino, Gaza y Cisjordania, fueron anexionados por Egipto y Transjordania, respectivamente. Al mismo tiempo, para los palestinos comenzaba la llamada Nakba o «catástrofe», con que se nombra el éxodo de entre 500 mil y un millón de palestinos que debieron desplazarse desde sus hogares hasta las zonas de palestina que quedaron bajo control árabe o bien debieron abandonar palestina.

En 1967, la Guerra de los Seis días volvería a correr las fronteras. Israel se enfrentó a los ejércitos de Egipto, Siria, Irak y Jordania. Las hostilidades nuevamente se resolvieron a favor del estado judío, que terminó conquistando Gaza, Jerusalén Este, Cisjordania, la península del Sinaí y los Altos del Golán. En 1973, Israel volvió a ganar en la ofensiva que lanzaron los ejércitos Siria y Egipto, conocida como Guerra del Yom Kipur. Por entonces ya se había formado la Organización de Liberación Palestina (OLP) y el Frente Popular para la Liberación de Palestina (FPLP) y el conflicto árabe-israelí se consolidaba como una suerte de estado de guerra permanente y transnacional. Así lo constataban los secuestros de aviones y atentados terroristas perpetrados por el FPLP y el grupo Septiembre Negro en diversos lugares del mundo, el ataque de las tropas jordanas a las bases de la OLP y la desastrosa Guerra del Líbano (1975-1990) que prácticamente destruyó al país que alguna vez fue conocido como la «Suiza de Medio Oriente», y que entre otras barbaridades nos legó las matanzas de Sabra y Chatila.

Por esa época comienza un ciclo de negociaciones y fracasos que se sostiene hasta hoy. Parte con la intervención de Yasir Arafat, presidente de la OLP, ante la asamblea de Naciones Unidas en 1974, sigue con los acuerdos de Camp David en 1978 y los acuerdos de Oslo de 199, que es lo más lejos que probablemente han llegado los acuerdos de paz, y que determinaron la creación de la Autoridad Nacional Palestina que se encargó de la administración de ciertas zonas de Cisjordania y Gaza. Pero el correlato de estos acuerdos han sido la primera (1987-1993) y segunda (2000-2005) Intifada o levantamientos populares palestinos contra la ocupación, y también una serie de brutales represalias militares de Israel, como las operaciones Plomo Fundido (2008-2009) y Pilar Defensivo (2012) sobre la Franja de Gaza. Desde el 2002, casi a modo de remate, la construcción por parte de Israel de un gran muro divisorio en Cisjordania, que en la mayoría de su trazado se adentra en Cisjordania más allá de la Línea Verde y que ha terminado por hacer más difícil el tránsito de los palestinos por los territorios ocupados, con las consecuencias sociales, ambientales, económicas y sanitarias que eso implica.

Líneas, colores, fechas y metáforas. Sólo los nombres de estas guerras, enfrentamientos, movimientos y operaciones bien reflejan que conflictos como éstos no sólo se pelean con armas, sino también en el nivel simbólico. Y por cierto que en el mapa, que es tanto un modo de conocimiento y dominio como un dispositivo de representación e imaginación, se juegan aspectos significativos y complejos de esta dimensión simbólica de nuestra realidad.

I. Lines of conflict

If we search the Internet for information that may elucidate the conflict between Palestinians and Israelis, at some point, we shall come across diverse maps on which intricate lines of different colors or intervals shall cross each other over and over again. These lines are an attempt at explaining the border between the Arab and Jewish states, whether this is according to the United Nation’s 1947 partition plan, the Green Line set by the 1949 Armistice Agreements, the territories occupied after the Six Day War, the areas under Palestinian administration after the Oslo Accords, or the wall that Israel has been constructing in the West Bank since 2002, amongst other possibilities.

Each line represents a convention, an agreement, or a position. These are lines that represent points of view that some deem worth killing and dying for. 13,000 kilometers, two continents, and one ocean away, these lines still signify antagonistic realities for many descendants and sympathizers of Arab and Jewish communities in this corner of South America. It is worth pointing out, and we shall come back to it, that the Chilean territory is home to the largest community of Palestinians outside of the Middle East.

Let us make a bit of history and go over the main lines of this conflict. The first important line is the one that defined the partition of Palestine, occupied by Great Britain since the end of World War I, and by the Ottoman Empire prior to that. It was determined by a narrow vote at the newly created United Nations Organization on November 29th, 1947, and defined the creation of two states in this territory: one Arab, and one Jewish. The partition was the result of relatively heterogeneous causes: Great Britain’s rush to pull out (its mandate had proved to be a failure, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to control the violence between Palestinian and Jewish communities); the complex diplomatic negotiations of a world that was in the process of recomposing its powers and balances after World War II (from those developed by the Jewish Agency to the sudden negotiation powers acquired by developing countries that were involved in the vote); lastly, the world had yet not recovered —how could it have?— from the shock of the extermination of over 6 million Jews in Nazi Germany, a fact that gave a sense of urgency and compensation to the creation of a Jewish state. This crowned half a century of the Zionist movement’s work, which had been pushing for the creation of the state of Israel since the XIX century.

.

.

With such pressure and on such diverse grounds, the 1947 partition was destined for conflict or failure. It handed 57% of the Palestinian territory over to a new Jewish state, in which over half of the population was Arab, and left Jerusalem (considered to be a Holy City by Jews, Christians, and Muslims) under the UN’s tutelage. It was unsurprising that the leaders of the 1,200,000 Palestinians that lived within the territories that were being divided did not accept this partition, as neither did the neighboring Arab states. Hence, on the same day that British troops withdrew from the territory, a bloody war broke out between the newly created Jewish state and the armies of Transjordan, Egypt, Syria and Iraq, as well as irregular militias and smaller contingents from Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, all of these acting as countries that did not recognize the newly created state of Israel.

The hostilities did not cease entirely until a year later, by when Israel’s victory was clear. The Green Line defined by the armistice increased Israel’s territory by 23% in comparison to the UN’s original partition. In spite of only gaining a portion of Jerusalem and failing to conquer the walled “Old City”, Israel declared this city as its capital. The rest of the Palestinian State, Gaza and the West Bank, were annexed by Egypt and Transjordania respectively. Around this point in history, Palestinians began to experience what they called Nakba or “catastrophe”: this was the name they gave to the exodus of somewhere between 500,000 and one million Palestinians who were forced to either leave their homes and head for areas of Palestine that were left under Arab control, or abandon Palestine completely.

In 1967, the Six Day War would shift the border once more. Israel fought against Egyptian, Syrian, Iraqi and Jordanian military forces. Once more, the hostilities were resolved in favor of the Jewish state, which ended up conquering Gaza, East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Sinai peninsula and Golan Heights. In 1973, Israel once more defeated the offensive led by Syrian and Egyptian troops, which was then known as the Yom Kippur War. By then, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) had already been formed, and the Arab-Israeli conflict was establishing itself as a state of permanent and transnational war. This was further consolidated by the airplane hijackings and terrorist attacks perpetrated by the FLPL and the Black September group in various places of the world, the Jordanian army attacks on PLO bases, and the disastrous Lebanese War (1975—1990) that practically destroyed the country that was once known as “the Switzerland of the Middle East”, and which, among other barbarities, gave us the massacres of Shabra and Shatila.

Around this time begins a cycle of negotiations and failures that carries on up until today. It starts with the intervention of Yasser Arafat, president of the PLO, at the United Nations General Assembly in 1974, then continues with the Camp David Accords in 1978 and the Oslo Accords in 1993. These latter agreements are probably the furthest the peace talks have ever gone, and determined the creation of the Palestinian National Authority, which took charge over the administration of certain areas in Gaza and the West Bank. But the correlate to these peace agreements have been the first (1987-1993) and second (2000-2005) Intifada, or Palestinian uprisings agains the occupation, as well as a series of brutal military retaliations from Israel, such as Operation Cast Lead (2008-2009), Operation Pillar of Defense (2012), and Operation Protective Edge (2014) on the Gaza Strip. Finally, since 2002, Israel has been building a large barrier in the West Bank, most of which stretches beyond the Green Line and has ended up making the Palestinians’ transit through the occupied territories more difficult, with the social, environmental, economic and sanitary consequences that this implies.

Lines, colors, dates, and metaphors. The names of these wars, confrontations, movements and operations alone reflect that conflicts like these fight not only with weapons, but also, on a symbolic level. And clearly, on a map, which is both a manner of knowledge and dominion, as a device for representation and imagination, is where the significative and complex aspects of this symbolic dimension of our reality are played out.