Las formas de amenaza

Christian ÁlvarezEl fenómeno de la vida no ocurre de forma aislada, sino en directa relación con el entorno que la acoge. El entorno permite que los distintos compuestos se ensamblen y formen organismos, y también liquida a aquellos que no logren un mínimo de adaptación. Sin embargo, habrá organismos que, para mantener su supervivencia, necesitarán y buscarán modificar su entorno y convertirlo así en un lugar más hospitalario. De esta forma, se asegura un bienestar para los integrantes de la comunidad, y también se genera un hábitat hostil para los que son percibidos como enemigos. Por lo tanto, organismos y ambientes se dejarán huellas mutuamente.

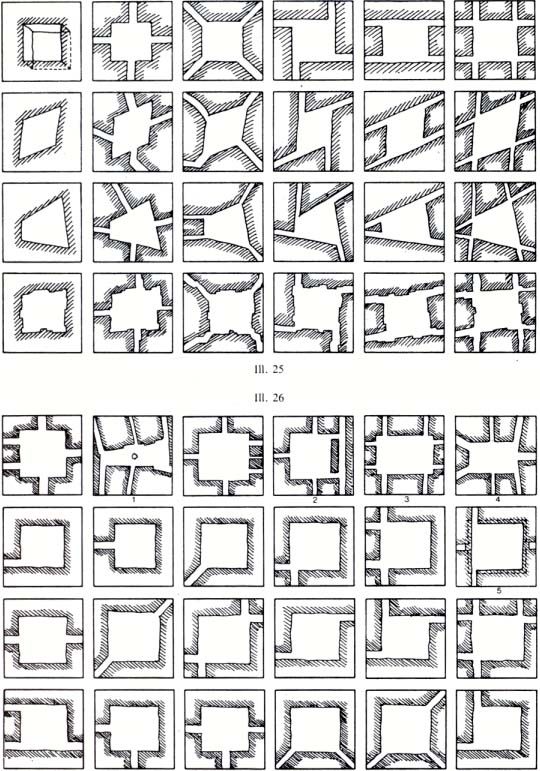

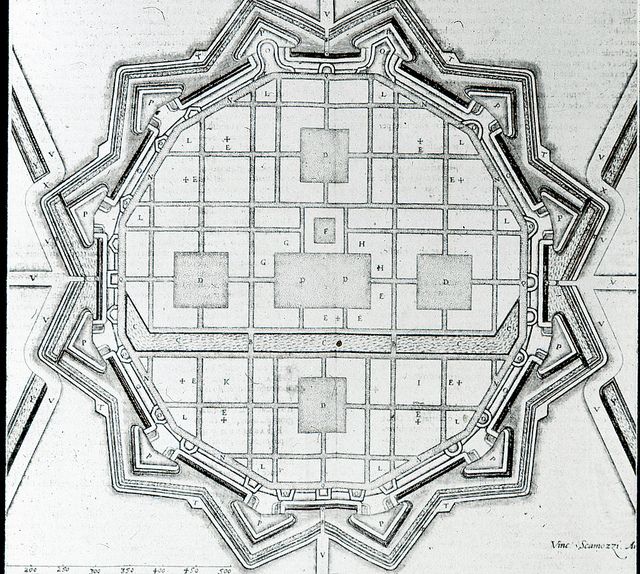

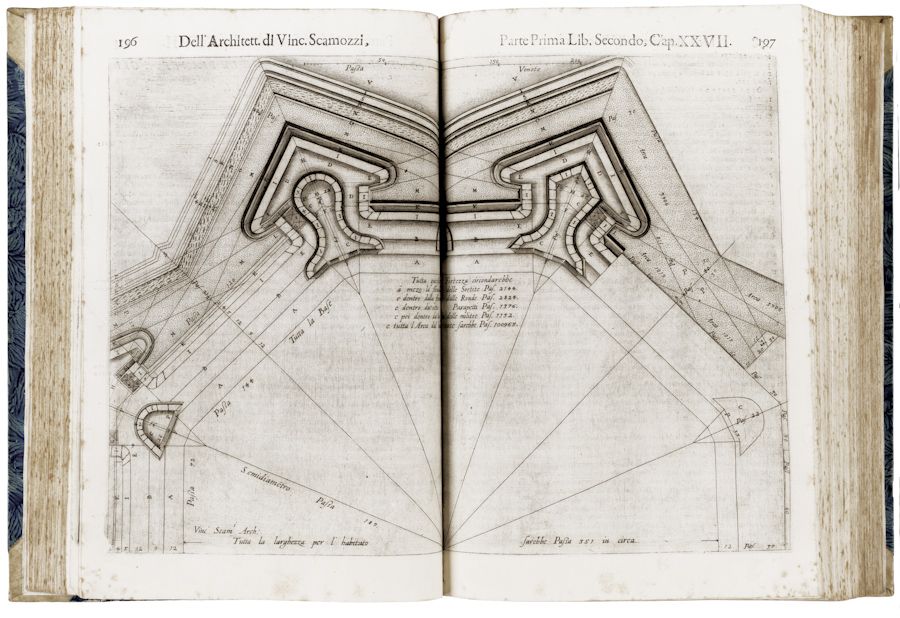

En algunos organismos, como los insectos, su estructura corporal evidencia la necesidad de apropiarse de un espacio y amenazar a quienes puedan interferir en sus planes. En otros organismos más complejos, compuestos por la interacción de múltiples individuos, las formas de disuasión y de reconfiguración del espacio serán a escala colectiva. Un ejemplo de este último caso son las sociedades humanas, y como refleja la recopilación de diseños de fortalezas renacentistas hecha por Rafael Guendelman, la necesidad de controlar un espacio va de la mano con formas que serán leídas por el forastero como amenazantes. Sin embargo, si consideramos que el diseño de la ciudad amurallada responde más a necesidades prácticas que a libertades creativas, podemos comprender que han sido factores históricos y antes evolutivos los que han posibilitado la emergencia de aspectos formales que, posteriormente, y aislados de su función material, pueden ser leídos como un código estético que será usado por el artista para explorar qué posibilidades tiene en el presente y en nuevos materiales. La simpleza original de las fortalezas renacentistas y su posterior complejización formal, puede leerse entonces como el aumento en las capacidades técnicas de las sociedades que las crearon, que pudieron extender sus construcciones en terrenos cada vez más irregulares, lo que a su vez de cuenta de mayores urgencias a la hora de resguardar el espacio habitable. Como si el temor a la invasión y el saqueo fuese un costo inseparable de los mayores recursos tecnológicos disponibles.

La indagación posterior que realizó Rafael en los diseños de rejas y estructuras disuasivas en Santiago, dan cuenta de una persistencia de este proceso evolutivo y estético de apropiación de un espacio, pero introduce además un importante factor cultural con sus respectivas consecuencias políticas. La proliferación en las últimas décadas de figuras cuya función es la amenaza de expulsión de un espacio, da cuenta de cómo el espacio que vale la pena defender pasó de ser la ciudad completa al propio hogar, como señal de un creciente individualismo promovido y forzado por decisiones políticas específicas, como el diseño de un sistema económico en que no hay sociedad, sino solo individuos y sus familias.

Esta transformación del paisaje urbano está anclada en la memoria de quienes hayan vivido los cambios políticos y económicos del último tramo histórico. Así, la infancia en barrios donde las rejas eran más un estorbo para las permanentes actividades comunitarias en vez de una protección sobre la propiedad, que por entonces podía ser bastante escuálida, dio paso a un presente en donde los televisores nuevos se pagaron no solo con largas cuotas, sino también con separar a la vivienda de su entorno, convirtiéndola en una pequeña fortaleza ahora amenazante para los mismos que antes fueron compañeros en la supervivencia diaria.

El trabajo pictórico y escultórico de Rafael Guendelman ofrece entonces la posibilidad de trazar una genealogía de las formas destinadas a la demarcación del territorio, con la capacidad de aislarlas para que, desprovistas de su uso cotidiano y desde una apreciación estética, nos puedan develar qué camino han seguido hasta llegar a nosotros, y si tenemos alguna opción de prescindir de ellas.

Forms of Threat

Christian ÁlvarezLife as a phenomenon does not occur in an isolated manner, but rather, in direct relation to the environment that it exists in. The environment allows different compounds to assemble themselves and form organisms, and liquidates those that fail to reach a minimum degree of adaptation. However, there are organisms that, in order to continue to survive, shall need and seek to modify their surroundings, thus turning the environment into a more hospitable place. In this way, the wellbeing of the community’s members is secured, and a hostile habitat is generated for those who are perceived as enemies. This is how organisms and environments leave mutual marks on each other.

In some organisms, such as insects, their body structures evidence the need to appropriate a space and threaten those who may interfere with their plans. In other more complex organisms, comprised of the interaction of multiple individuals, the forms of dissuasion and reconfiguration of space occur on a collective scale. An example of this latter case are human societies, and as the compilation of designs of Renaissance fortresses made by Rafael Guendelman reflects, the need to control a space goes hand in hand with forms that an outsider shall read as threatening. However, if we consider that the design of a walled city responds more to practical needs than to creative liberties, we can understand that there have been historical factors, and prior to that, evolutionary ones, that have enabled the emergence of formal aspects that, subsequently and isolated from their material function, can be read as an aesthetic code that the artist shall use to explore their possibilities in the present and with new materials. The original simplicity of Renaissance fortresses and their subsequent increase in formal complexity can thus be read as the increase of the technical capacities of the societies that created them, which were able to extend their constructions over increasingly irregular terrains, which in turn reveals a greater urgency when it comes to securing habitable space. It’s as if the fear of invasion and looting was a cost that is inseparable from the greatest technological resources available.

Rafael’s subsequent inquiry into the designs of fences and dissuasive structures in Santiago reveals a persistence in this evolutive and aesthetic process through which a space is appropriated. It also introduces an important cultural factor, with its respective political consequences. The proliferation over the past decades of figures whose function is to threaten with expulsion from a place is a sign of how the space that is worth defending went from being the entire city to one’s own home, as an indication of growing individualism, encouraged and forced by specific political decisions, such as the design of an economic system in which there is no society, just individuals and their families.

This transformation of the urban landscape is anchored in the memory of those who have experienced the political and economic changes of this latest period in history. In this way, childhood memories of neighborhoods in which fences were more of an obstacle for permanent community activity instead of a way of protecting property, which back then could be quite meager, gave way to a present in which new television sets are being paid not only in lengthy installments, but also by separating a house from its surroundings, turning it into a small fortress that is now menacing to the same people who were once companions in day-to-day survival.

Rafael Guendelman’s pictorial and sculptural work thus offers the possibility of tracing a genealogy of the forms that are destined for the demarcation of territory, with the capacity of isolating them so that, stripped of their everyday use and from an aesthetic appreciation, they may reveal the path that they have followed until reaching us, and whether we have any options of renouncing them.